John Morra's still life paintings have an architectural quality. In Mertz No. 7, above, our horizon line is level with the table surface. A Bladerunner landscape for ants. You can easily see that the items on the table are subject to the same laws of perspective that define the optical perception of buildings. The effect is magnified by placing the standpoint very close to the picture plane, creating an intimate effect. It's a cityscape in microcosm.

Perspective is just as important when dealing with objects in a still life as when painting a landscape.

Morra is a master of empirical observation, so I was curious when I saw his Still Life with Vessels, Pestles and Red Masher, 2008, (above) and noticed that the perspective of the saucepan on the left seems out of play with the rest of the elements in the painting. Again we are level with the tabletop, and are looking up at the upper rims of the vessels, yet the saucepan seems oddly tipped towards us.

I received a commission to paint a still life of antique medical implements, and chose to treat the composition similarly. This painting was to be viewed across a room, so I pulled the viewpoint back from the picture plane and raised the horizon line.

Unfortunately, the Ostrich and Kiwi eggs and the pile of books were the only items that weren't taken from a photographic internet reference, and the result is kind of lifeless and unnatural. It finally occurred to me that it's necessary to pay attention to the real world!

That's why it bothered me so much when I came across possibly the worst book ever on Perspective. Billing itself as a 'detailed training course,' it is peppered with snapshots of Italy and dares in the introduction to reference the treatises of Leon Battista Alberti and Filippo Brunelleschi, presumably to add a whiff of European old-world credibility. Do not buy this book. I'll use it as a jumping off point for a quick demonstration.

Here's an illustration from the book. They're trying to explain how to draw a 'flattened oval'. Presumably they mean an ellipse (a cone intersected by a plane), which is in effect a somewhat flattened circle. I overlaid a perfect red ellipse in Photoshop.

Here's how to show the perspective a little more clearly. First, I created a circle in red, overlaid on a grid.

Then I tilted the plane to simulate the effect of a circle lying on the ground directly in front of the viewer.

The book uses the following illustration in an attempt to show how a circle will optically flatten the closer it gets to the horizon line, until it eventually becomes a flat line. This is true, though their drawing is inaccurate and crude.

It then goes on to give an illustration of a bottle, and completely ignores this lesson. The bottle shown has two horizon lines; something I've never come across in nature. I drew the red lines to show the error: the bottom of the bottle has a vanishing point at VP 2, and the imaginary ellipse at the top vanishes at VP 1....Huh?

Okay, I went ahead and re-sketched their bottle a little more accurately to demonstrate what we've observed in Morra's work and what the author seems to have forgotten: that objects on a table-top adhere to the same rules of graphical perspective as the rest of the Universe, oddly enough.

At this point, we better take a look at what a Master had to say on the subject. This drawing pretty much ends all conversation on the matter. It's Uccello's drawing of a vase.

Not bad! [Uccello has positioned the viewer far from the vase]. You may also be interested in Uccello's drawing of a dodecahedron that I posted elsewhere on this blog.

Artist Adam Forfang is a painter of still lifes, among other things. Here's a detail from one of his paintings. I overlaid the red ellipses and grid to demonstrate that the horizon line is at the top of the bottle, and how the ellipses of the bottle seem to 'open up' the further they are from the horizon.

Pretty simple so far, right?

Let's look at a perspective of a polygon from the same book, and you'll see that it's evidently not so easy if so-called teachers can't get it right.

They start from this photograph. A difficult three-point perspective street-scape, and that's without taking the eight-sided polygon (octagon) of the fountain base into account. Tricky.

They then blunder into a sloppy attempt to render this graphically.

It's so bad I don't even know where to begin. I guess I could tear out the pages and use them to clean up after my daughter's Guinea Pigs. First I drew an octagon on a grid. You can see that the opposite edges are parallel.

Then I tilted it down directly in front of the viewer. The horizon line is marked. You can see that each pair of parallel sides has a common vanishing point. Each VP converges naturally on the horizon line.

"Ah", you say, "but what if I'm not standing directly in front of the fountain, as in the photograph?"

This time, before we tilt the grid down, we rotate the polygon however much you want. In this case, I rotated it an eighth. Then I tilted it down. The parallel sides still have Vanishing Points that converge on the horizon line [sides 4 & 8 also have a VP that's way off to the right]. VP 1 represents our new vantage point, as we have taken a couple of steps to the left of the center of the fountain.

Here's how Luciano Testoni drew an octagon and extruded it.

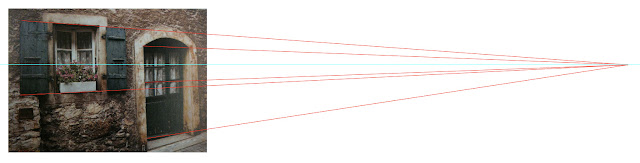

This is another photo from the book, used as reference for a different lesson.

The author goes on to say that this is basically one-point perspective, with the vanishing point off to the right somewhere. This is inaccurate. The recessed doorway and windows have their own (second) vanishing point, and the wide-angle lens used for this snapshot has created a third perspective wherein the vertical lines of the photograph converge somewhere off the top of the image. Let's ignore that effect due to distortion for now, but the second perspective of the door recesses is important to understand.

Muralists and trompe l'oeil painters will regularly have to work out just this kind of issue in their work.

Trying to find the vanishing point and horizon out to the right was complicated a little by the fact that the house is on a hill, so the ground and door saddle have a different vanishing point all their own.

Here is the second vanishing point that we are concerned with, out to the left.

Now let's draw our own version of the arched doorway. I straightened the vertical lines, as one would expect to see in a Mural, to give us a simpler two-point perspective rendering.

A close-up of the window shows the construction lines more clearly.

Okay so far, but the archway at the top of the door poses a small problem: How do we correctly draw the back of the arch in perspective?

Again, this is a very typical scenario, and has many applications. First, let's draw an ellipse (in blue) that conforms to the section of the arch that we can see. The red dotted line is the center line of the ellipse. A red dot marks the center of our ellipse.

The red line going back to VP 1, and passing across point (b), will intersect our dotted center line of the ellipse. From that intersection point, draw a line receding to VP 2 [line shown in green, below].

To do that, we draw another red line coming from VP 1, and passing though point (a). Where it intersects the top green line (at the X), drop a dotted line down to the bottom green line.

This will be the center of the back ellipse. Create a copy of the ellipse, and slide it back along the green line until it is centered over that point. With me?

Okay, now we need to scale down our ellipse. As you know, objects appear to shrink in size the further way from us they get. Our ellipse is too big.

Scale it down evenly through it's center point until it's edge touches point (a):

Done! Now simply remove all the excess lines, and you have a properly rendered doorway in perspective.

Nice job- do you teach classes?

ReplyDeletegreat article :)

ReplyDeleteSteve, for years it's been in the back of my mind, but I have been giving it more serious thought since starting to write the blog. Writing and sharing has been a lot of fun for me, so who knows...

ReplyDeletewow, have to remember this life lesson. its not always my fault when i dont understand the lesson. it very much depends on how well the teacher understands the subject. thank you for taking the time to explain this so well.

ReplyDeleteWow! I just stumbled across your blog! I'm dumbfounded and happy to have found such an informative, enriching and useful blog. Thank you! If you're not a teacher, you should be!

ReplyDeleteI took a beginners drawing class and the prof. didn't explain and demonstrate perspective as well as you did here. You really should consider teaching or writing a book with DVD yourself.

ReplyDeleteGreat examples. May I use a couple of images to include on a power point for drawing students. I will give you credit. what is yourname?

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing, nice post! Post really provice useful information!

ReplyDeleteHương Lâm chuyên cung cấp máy photocopy và dịch vụ cho thuê máy photocopy giá rẻ, uy tín TP.HCM với dòng máy photocopy toshiba và dòng máy photocopy ricoh uy tín, giá rẻ.